- A few non-travel-related malaria cases were reported last month in Florida and Texas.

- Although there is an approved vaccine to protect against malaria, it is currently unavailable in the United States.

- Vaccines have been in development for decades, but progress has been slow.

- The risk of contracting malaria in the United States remains low.

At the end of June, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a health advisory, stating that five malaria cases had been identified in the United States.

Four were in Florida and one was in Texas. None of the cases were related to international travel.

Malaria is a life-threatening illness that occurs when a person is bitten by a mosquito with the disease. Symptoms range from high fever and vomiting to bloody stools and anemia. Untreated, it can be potentially life-threatening.

Around 5 people die in the United States each year from malaria. In comparison, roughly 594,240 people in Africa died from malaria in 2021 — accounting for 96% of worldwide mortalities.

Following on from the recent cluster of cases in the southern United States, here’s what to know about malaria vaccinations.

How a malaria vaccine works

Currently, there is no malaria vaccine the United States and there isn’t expected to be one any time soon.

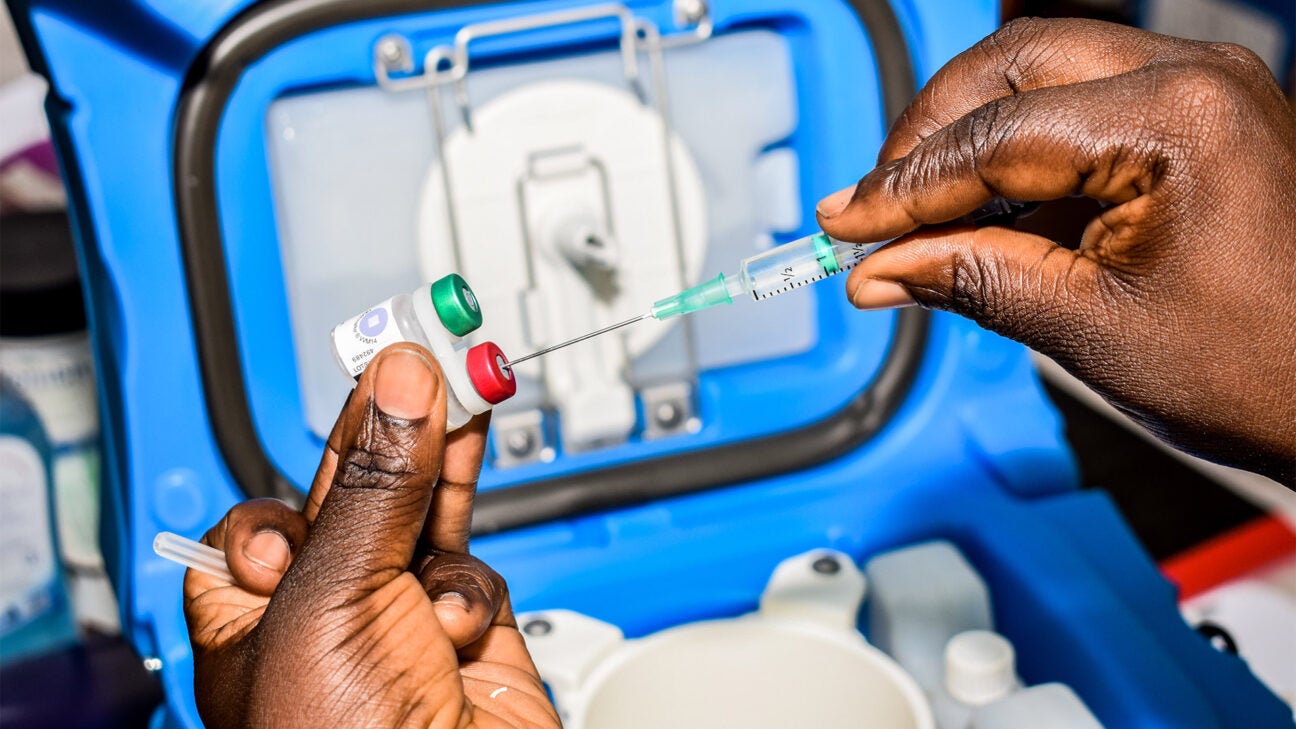

Only one vaccination is approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) for malaria, RTS,S/AS01. It is designed for and available to children in Sub-Saharan African countries where malaria is common in infants and related deaths are high.

RTS,S/AS01 is designed to protect against a malaria parasite called Plasmodium falciparum, which “causes the most severe form of malaria and death,” stated Dr. Sherrill Brown, the medical director of infection prevention at AltaMed Health Services.

“The vaccine contains a piece of the malaria parasite that initiates antibody formation in people that receive the vaccine,” Brown told Healthline.

“Those antibodies can then attack and neutralize the malaria parasite that gets into the body before it infects the liver and causes severe infection,” she added.

Why there isn’t a malaria vaccine in the United States

So why isn’t the vaccine available in the United States?

Essentially, the risk of contracting malaria on U.S. soil is nowhere near high enough to warrant widespread immunization, said Dr. Eyal Lesham, the director of the Centre for Travel Medicine and Tropical Diseases at Sheba Medical Centre and a professor of internal medicine and infectious diseases at Tel Aviv University in Israel.

“It is really country-specific or region-specific, whether or not to use a malaria vaccine. The risk for contracting and developing severe disease and dying of malaria is substantially lower in other regions around the world,” he told Healthline.

When it comes to vaccinations, public health officials prioritize immunizing against diseases and illnesses that are more common in specific areas.

Lesham added that — unlike people in Africa — most of those in the United States who contract malaria “will have rapid access to a well-equipped emergency room, where they can be tested and treated.”

It’s also worth noting that the recent malaria outbreak “clusters” involved a different malaria species called P. vivax, said Dr. Larry Kociolek, an attending physician of infectious diseases at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and member of the HRSA-funded Pediatric Pandemic Network.

“Therefore, this vaccine would not prevent the cases acquired in the US,” he told Healthline.

Why the recent malaria outbreak occurred

Around 2,000 malaria cases are diagnosed and treated in the United States each year. However, these are typically linked to travel to regions where malaria incidence is high, such as Sub-Saharan Africa.

The 5 recent cases, however, were not linked to international travel. It’s unclear exactly how these individuals were bitten by an infected mosquito.

“The infected mosquito could be a mosquito that hitchhiked on an airplane, or a local mosquito that bit someone else who had malaria and then bit the person who never traveled,” said Dr. Andrea A. Berry, an associate professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health.

“In Florida, infected mosquitoes have been found, so this suggests that the people with malaria in Florida were bitten by local mosquitoes that are infected. In the one Texas case, it is harder to know,” she told Healthline.

People in the United States should not be too concerned about further cases, stated Berry. Not only are outbreaks rare, but malaria is not contagious and cannot be passed from person to person.

“There has already been an appropriate public health response to the cases that have occurred,” she said.

“Warnings have been publicized, public health officials are determining where the infected people were during the window when they were infected, [and] there has been mosquito surveillance and spraying in the relevant areas,” Berry added.

The challenges in developing malaria vaccines

Scientists have been trying for decades to formulate and roll out vaccines that reduce malaria risk, but progress has been slow.

In fact, it took almost 30 years for RTS,S/AS01 to be developed and approved.

Advancements have been slow for various reasons.

The primary factor, explained Lesham, is that all current vaccines target viruses and bacteria. However, parasites are an entirely different organism and have a different biology.

“The way these parasites evade the immune system is more sophisticated,” he said. “Therefore, developing an effective vaccine is and remains a major challenge.”

Such hurdles in awareness and disease mechanisms have meant that, while the RTS,S/AS01 is “very safe,” assured Lesham, it’s “not as effective as we were hoping” — with an efficacy rate of around 30%.”

Dr. John Mourani, the medical director of infectious diseases at Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center in California, noted that “in general, developing a vaccine is a challenge,” as scientists are trying to create a solution that is simultaneously effective and safe.

Another challenge hindering development is the fact that studies to test vaccinations are “complex and expensive,” said Berry. Financial barriers also play a role, particularly as malaria isn’t a disease commonly affecting those in higher-income countries.

“The previous lack of generous and sustained investment in a disease not commonly encountered in areas of the world with higher income initially slowed progress in malaria vaccine development,” Kociolek said.

Despite this, research into malaria vaccinations continues.

Last year, scientists at the University of Maryland School of Medicine reported that three doses of the Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite (PfSPZ) vaccine had efficacy rates up to 48% six months after injections and up to 46% after 18 months.

The PfSPZ vaccine targets the same strain of malaria parasite as the RTS,S/AS01 vaccination. However, while the RTS,S/AS01 formula needs to be kept at a temperature between 2℃ and 8℃, the “PfSPZ vaccine has to be stored at ultra-low temperatures [between -150℃ and -196℃], which [is a] logistical challenge,” Berry noted.

Storage logistics aside, the 2022 research into the PfSPZ offered promising results. However, for the vaccine to become widely used, “it needs to be at least as efficacious as other available vaccines, so we will need to see results of larger trials currently in development,” said Berry.

“This will take some time, but I am very interested to see the results,” she added.

Protecting yourself from malaria

Kociolek assured that “the risk of malaria to those living in the U.S. is exceedingly low.”

However, Brown said there are other mosquito-borne illnesses in the United States that we need to protect ourselves from — such as West Nile virus and St. Louis encephalitis — by “using similar preventive strategies.”

Some of these include:

- Wearing effective and safe mosquito-repellent when outdoors.

- Wearing loose-fitting clothing that covers the arms, legs, and ankles.

- Wearing enclosed shoes.

- Placing screens on windows and doors.

- Sleeping under a mosquito net.

Ultimately, the best way to avoid catching malaria is to not visit countries where the disease is endemic. If you need to travel to such regions, seek advice from your doctor before doing so, Lesham recommended, and “take malaria prophylaxis, which are pills that are meant to prevent you from contracting malaria.”

If you return from a country where malaria rates are high and start experiencing a fever, don’t hesitate to visit the emergency room, said Lesham.

“Mention your recent travel and ask for a malaria smear. Malaria is a type of disease where you feel well and then crash very rapidly,” he said.

Why a Malaria Vaccine Isn't Available in the United States

Source: Pinoy Lang Sakalam

0 (mga) komento:

Mag-post ng isang Komento